Chapter 6. I/O system

Chapter 6. I/O system

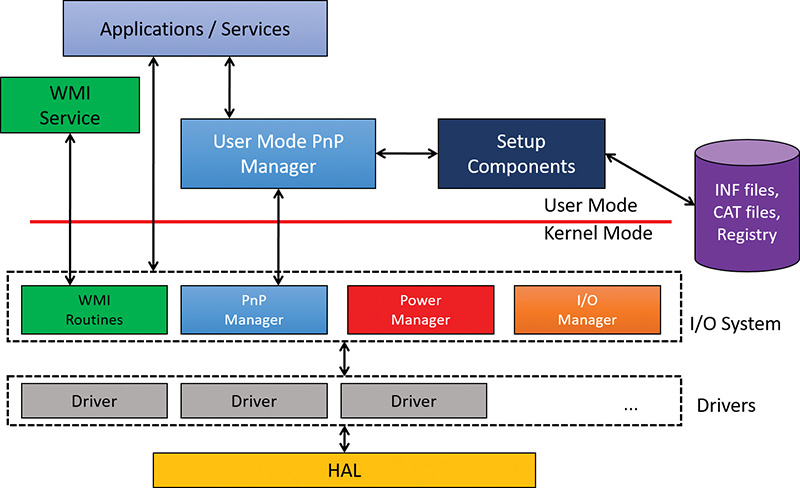

The Windows I/O system consists of several executive components that, together, manage hardware devices and provide interfaces to hardware devices for applications and the system. This chapter lists the design goals of the I/O system, which have influenced its implementation. It then covers the components that make up the I/O system, including the I/O manager, Plug and Play (PnP) manager, and power manager. Then it examines the structure and components of the I/O system and the various types of device drivers. It discusses the key data structures that describe devices, device drivers, and I/O requests, after which it describes the steps necessary to complete I/O requests as they move through the system. Finally, it presents the way device detection, driver installation, and power management work.

I/O system components

The design goals for the Windows I/O system are to provide an abstraction of devices, both hardware (physical) and software (virtual or logical), to applications with the following features:

![]() Uniform security and naming across devices to protect shareable resources. (See Chapter 7, “Security,” for a description of the Windows security model.)

Uniform security and naming across devices to protect shareable resources. (See Chapter 7, “Security,” for a description of the Windows security model.)

![]() High-performance asynchronous packet-based I/O to allow for the implementation of scalable applications.

High-performance asynchronous packet-based I/O to allow for the implementation of scalable applications.

![]() Services that allow drivers to be written in a high-level language and easily ported between different machine architectures.

Services that allow drivers to be written in a high-level language and easily ported between different machine architectures.

![]() Layering and extensibility to allow for the addition of drivers that transparently modify the behavior of other drivers or devices, without requiring any changes to the driver whose behavior or device is modified.

Layering and extensibility to allow for the addition of drivers that transparently modify the behavior of other drivers or devices, without requiring any changes to the driver whose behavior or device is modified.

![]() Dynamic loading and unloading of device drivers so that drivers can be loaded on demand and not consume system resources when unneeded.

Dynamic loading and unloading of device drivers so that drivers can be loaded on demand and not consume system resources when unneeded.

![]() Support for Plug and Play, where the system locates and installs drivers for newly detected hardware, assigns them hardware resources they require, and allows applications to discover and activate device interfaces.

Support for Plug and Play, where the system locates and installs drivers for newly detected hardware, assigns them hardware resources they require, and allows applications to discover and activate device interfaces.

![]() Support for power management so that the system or individual devices can enter low-power states.

Support for power management so that the system or individual devices can enter low-power states.

![]() Support for multiple installable file systems, including FAT (and its variants, FAT32 and exFAT), the CD-ROM file system (CDFS), the Universal Disk Format (UDF) file system, the Resilient File System (ReFS), and the Windows file system (NTFS). (See Chapter 13, “File systems,” in Part 2 of this book for more specific information on file system types and architecture.)

Support for multiple installable file systems, including FAT (and its variants, FAT32 and exFAT), the CD-ROM file system (CDFS), the Universal Disk Format (UDF) file system, the Resilient File System (ReFS), and the Windows file system (NTFS). (See Chapter 13, “File systems,” in Part 2 of this book for more specific information on file system types and architecture.)

![]() Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) support and diagnosability so that drivers can be managed and monitored through WMI applications and scripts. (WMI is described in Chapter 9, “Management mechanisms,” in Part 2.)

Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) support and diagnosability so that drivers can be managed and monitored through WMI applications and scripts. (WMI is described in Chapter 9, “Management mechanisms,” in Part 2.)

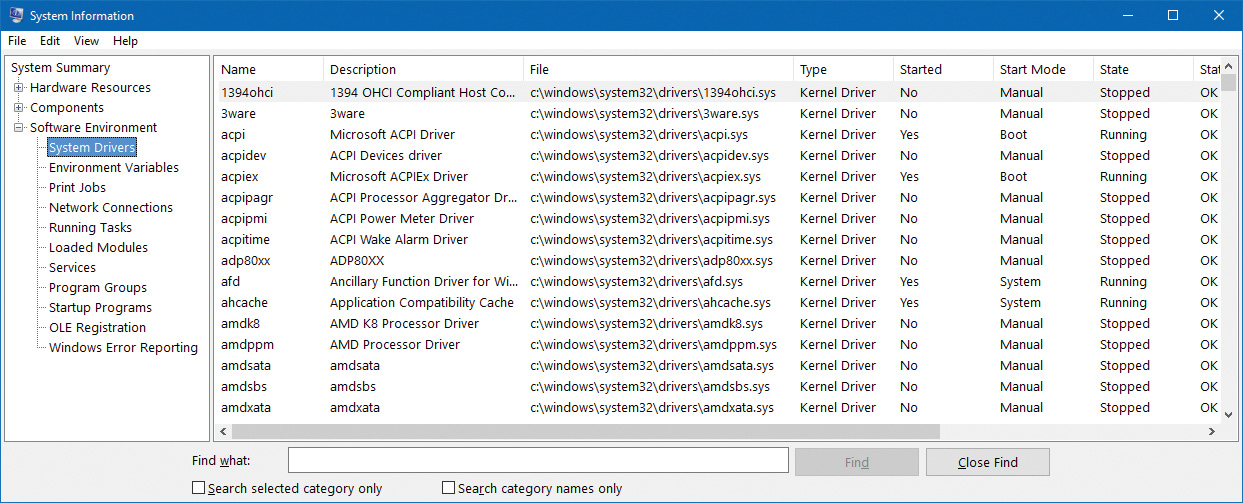

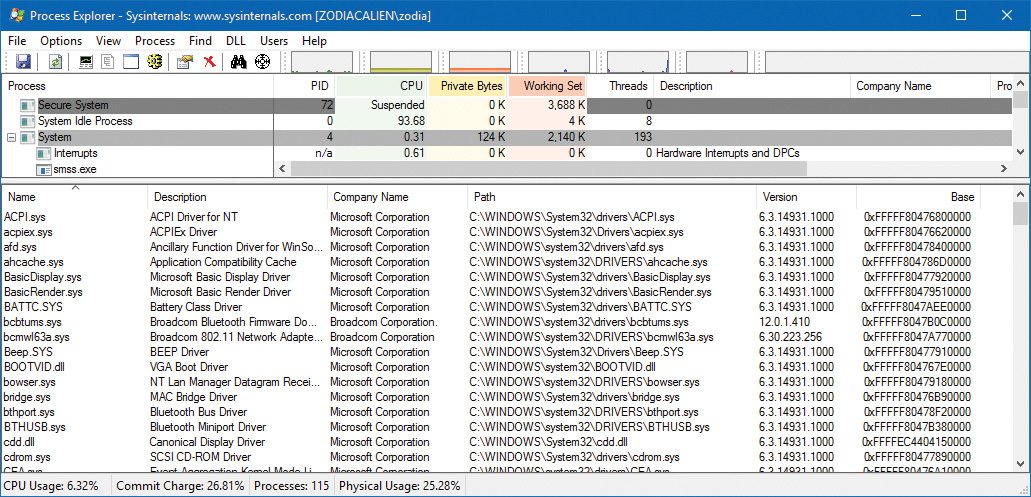

To implement these features, the Windows I/O system consists of several executive components as well as device drivers, which are shown in Figure 6-1.

![]() The I/O manager is the heart of the I/O system. It connects applications and system components to virtual, logical, and physical devices, and it defines the infrastructure that supports device drivers.

The I/O manager is the heart of the I/O system. It connects applications and system components to virtual, logical, and physical devices, and it defines the infrastructure that supports device drivers.

![]() A device driver typically provides an I/O interface for a particular type of device. A driver is a software module that interprets high-level commands, such as read or write commands, and issues low-level, device-specific commands, such as writing to control registers. Device drivers receive commands routed to them by the I/O manager that are directed at the devices they manage, and they inform the I/O manager when those commands are complete. Device drivers often use the I/O manager to forward I/O commands to other device drivers that share in the implementation of a device’s interface or control.

A device driver typically provides an I/O interface for a particular type of device. A driver is a software module that interprets high-level commands, such as read or write commands, and issues low-level, device-specific commands, such as writing to control registers. Device drivers receive commands routed to them by the I/O manager that are directed at the devices they manage, and they inform the I/O manager when those commands are complete. Device drivers often use the I/O manager to forward I/O commands to other device drivers that share in the implementation of a device’s interface or control.

![]() The PnP manager works closely with the I/O manager and a type of device driver called a bus driver to guide the allocation of hardware resources as well as to detect and respond to the arrival and removal of hardware devices. The PnP manager and bus drivers are responsible for loading a device’s driver when the device is detected. When a device is added to a system that doesn’t have an appropriate device driver, the executive Plug and Play component calls on the device-installation services of the user-mode PnP manager.

The PnP manager works closely with the I/O manager and a type of device driver called a bus driver to guide the allocation of hardware resources as well as to detect and respond to the arrival and removal of hardware devices. The PnP manager and bus drivers are responsible for loading a device’s driver when the device is detected. When a device is added to a system that doesn’t have an appropriate device driver, the executive Plug and Play component calls on the device-installation services of the user-mode PnP manager.

![]() The power manager also works closely with the I/O manager and the PnP manager to guide the system, as well as individual device drivers, through power-state transitions.

The power manager also works closely with the I/O manager and the PnP manager to guide the system, as well as individual device drivers, through power-state transitions.

![]() WMI support routines, called the Windows Driver Model (WDM) WMI provider, allow device drivers to indirectly act as providers, using the WDM WMI provider as an intermediary to communicate with the WMI service in user mode.

WMI support routines, called the Windows Driver Model (WDM) WMI provider, allow device drivers to indirectly act as providers, using the WDM WMI provider as an intermediary to communicate with the WMI service in user mode.

![]() The registry serves as a database that stores a description of basic hardware devices attached to the system as well as driver initialization and configuration settings. (See the section “The registry” in Chapter 9 in Part 2 for more information.)

The registry serves as a database that stores a description of basic hardware devices attached to the system as well as driver initialization and configuration settings. (See the section “The registry” in Chapter 9 in Part 2 for more information.)

![]() INF files, which are designated by the .inf extension, are driver-installation files. INF files are the link between a particular hardware device and the driver that assumes primary control of that device. They are made up of script-like instructions describing the device they correspond to, the source and target locations of driver files, required driver-installation registry modifications, and driver-dependency information. Digital signatures that Windows uses to verify that a driver file has passed testing by the Microsoft Windows Hardware Quality Labs (WHQL) are stored in .cat files. Digital signatures are also used to prevent tampering of the driver or its INF file.

INF files, which are designated by the .inf extension, are driver-installation files. INF files are the link between a particular hardware device and the driver that assumes primary control of that device. They are made up of script-like instructions describing the device they correspond to, the source and target locations of driver files, required driver-installation registry modifications, and driver-dependency information. Digital signatures that Windows uses to verify that a driver file has passed testing by the Microsoft Windows Hardware Quality Labs (WHQL) are stored in .cat files. Digital signatures are also used to prevent tampering of the driver or its INF file.

![]() The hardware abstraction layer (HAL) insulates drivers from the specifics of the processor and interrupt controller by providing APIs that hide differences between platforms. In essence, the HAL is the bus driver for all the devices soldered onto the computer’s motherboard that aren’t controlled by other drivers.

The hardware abstraction layer (HAL) insulates drivers from the specifics of the processor and interrupt controller by providing APIs that hide differences between platforms. In essence, the HAL is the bus driver for all the devices soldered onto the computer’s motherboard that aren’t controlled by other drivers.

The I/O manager

The I/O manager is the core of the I/O system. It defines the orderly framework, or model, within which I/O requests are delivered to device drivers. The I/O system is packet driven. Most I/O requests are represented by an I/O request packet (IRP), which is a data structure that contains information completely describing an I/O request. The IRP travels from one I/O system component to another. (As you’ll discover in the section “Fast I/O,” fast I/O is the exception; it doesn’t use IRPs.) The design allows an individual application thread to manage multiple I/O requests concurrently. (For more information on IRPs, see the section “I/O request packets” later in this chapter.)

The I/O manager creates an IRP in memory to represent an I/O operation, passing a pointer to the IRP to the correct driver and disposing of the packet when the I/O operation is complete. In contrast, a driver receives an IRP, performs the operation the IRP specifies, and passes the IRP back to the I/O manager, either because the requested I/O operation has been completed or because it must be passed on to another driver for further processing.

In addition to creating and disposing of IRPs, the I/O manager supplies code that is common to different drivers and that the drivers can call to carry out their I/O processing. By consolidating common tasks in the I/O manager, individual drivers become simpler and more compact. For example, the I/O manager provides a function that allows one driver to call other drivers. It also manages buffers for I/O requests, provides timeout support for drivers, and records which installable file systems are loaded into the operating system. There are about 100 different routines in the I/O manager that can be called by device drivers.

The I/O manager also provides flexible I/O services that allow environment subsystems, such as Windows and POSIX (the latter is no longer supported), to implement their respective I/O functions. These services include support for asynchronous I/O that allow developers to build scalable, high-performance server applications.

The uniform, modular interface that drivers present allows the I/O manager to call any driver without requiring any special knowledge of its structure or internal details. The operating system treats all I/O requests as if they were directed at a file; the driver converts the requests from requests made to a virtual file to hardware-specific requests. Drivers can also call each other (using the I/O manager) to achieve layered, independent processing of an I/O request.

Besides providing the normal open, close, read, and write functions, the Windows I/O system provides several advanced features, such as asynchronous, direct, buffered, and scatter/gather I/O, which are described in the “Types of I/O” section later in this chapter.

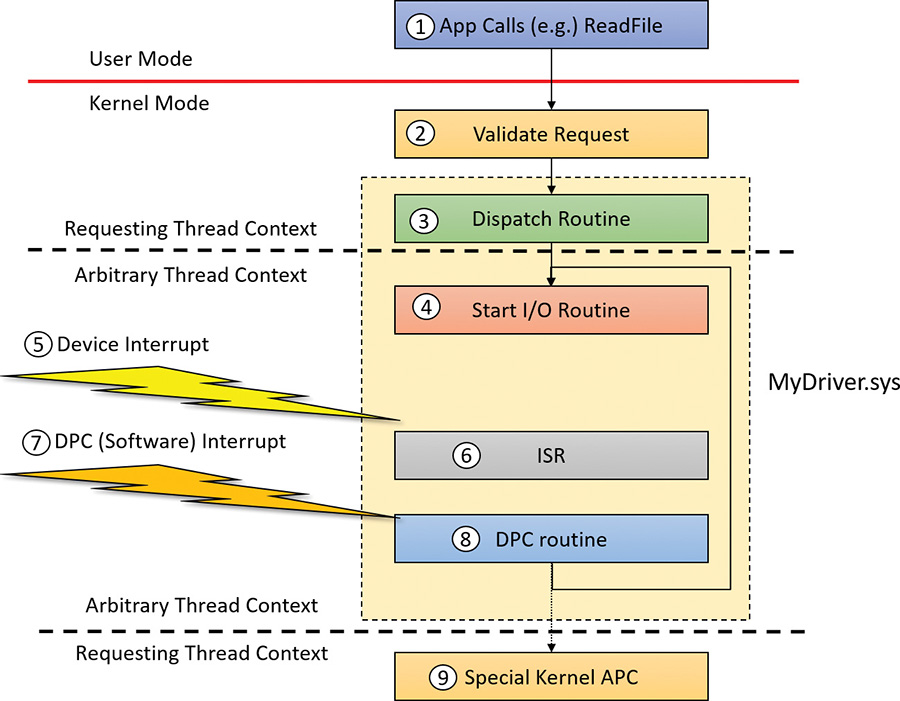

Typical I/O processing

Most I/O operations don’t involve all the components of the I/O system. A typical I/O request starts with an application executing an I/O-related function (for example, reading data from a device) that is processed by the I/O manager, one or more device drivers, and the HAL.

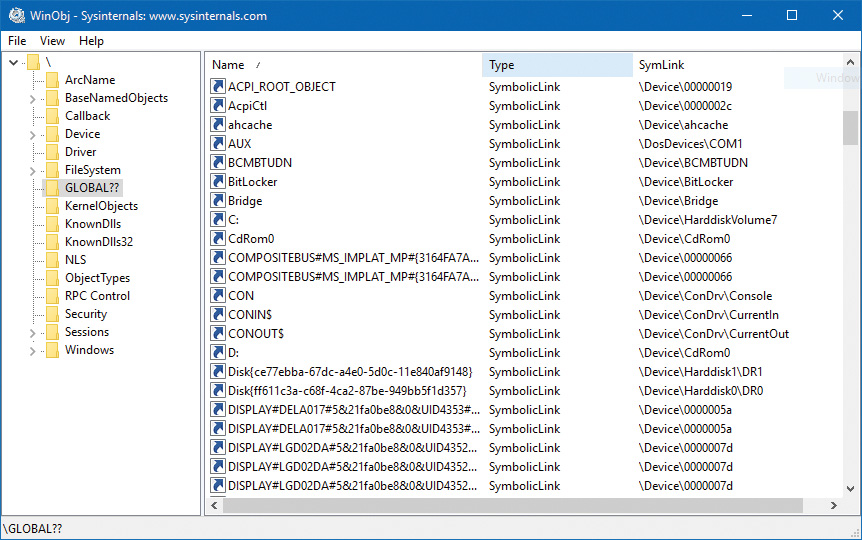

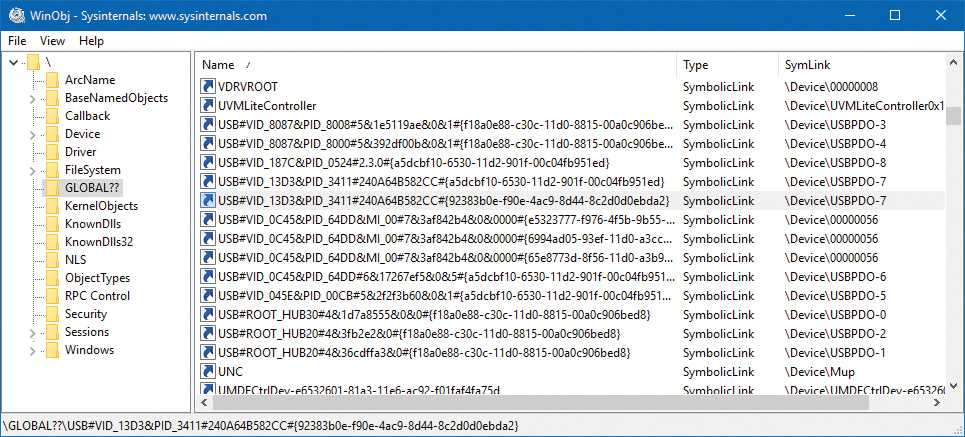

As mentioned, in Windows, threads perform I/O on virtual files. A virtual file refers to any source or destination for I/O that is treated as if it were a file (such as devices, files, directories, pipes, and mailslots). A typical user mode client calls the CreateFile or CreateFile2 functions to get a handle to a virtual file. The function name is a little misleading—it’s not just about files, it’s anything that is known as a symbolic link within the object manager’s directory called GLOBAL??. The suffix “File” in the CreateFile* functions really means a virtual file object (FILE_OBJECT) that is the entity created by the executive as a result of these functions. Figure 6-2 shows a screenshot of the WinObj Sysinternals tool for the GLOBAL?? directory.

As shown in Figure 6-2, a name such as C: is just a symbolic link to an internal name under the Device object manager directory (in this case, \Device\HarddiskVolume7). (See Chapter 8, “System mechanisms,” in Part 2 for more on the object manager and the object manager namespace.) All the names in the GLOBAL?? directory are candidates for arguments to CreateFile(2). Kernel mode clients such as device drivers can use the similar ZwCreateFile to obtain a handle to a virtual file.

![]() Note

Note

Higher-level abstractions such as the .NET Framework and the Windows Runtime have their own APIs for working with files and devices (for example, the System.IO.File class in .NET or the Windows.Storage.StorageFile class in WinRT), but these eventually call CreateFile(2) to get the actual handle they hide under the covers.

![]() Note

Note

The GLOBAL?? object manager directory is sometimes called DosDevices, which is an older name. DosDevices still works because it’s defined as a symbolic link to GLOBAL?? in the root of the object manager’s namespace. In driver code, the ?? string is typically used to reference the GLOBAL?? directory.

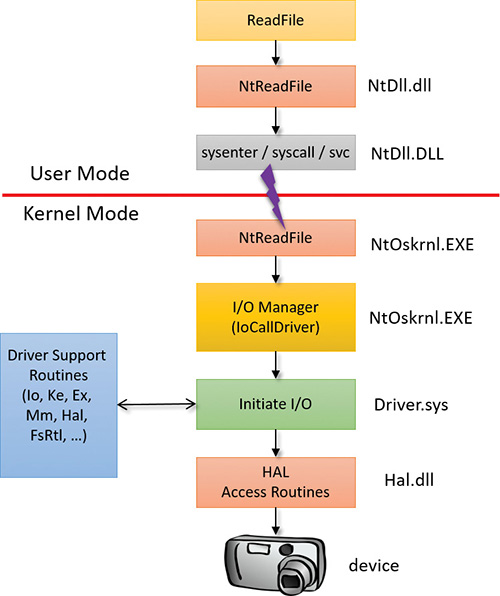

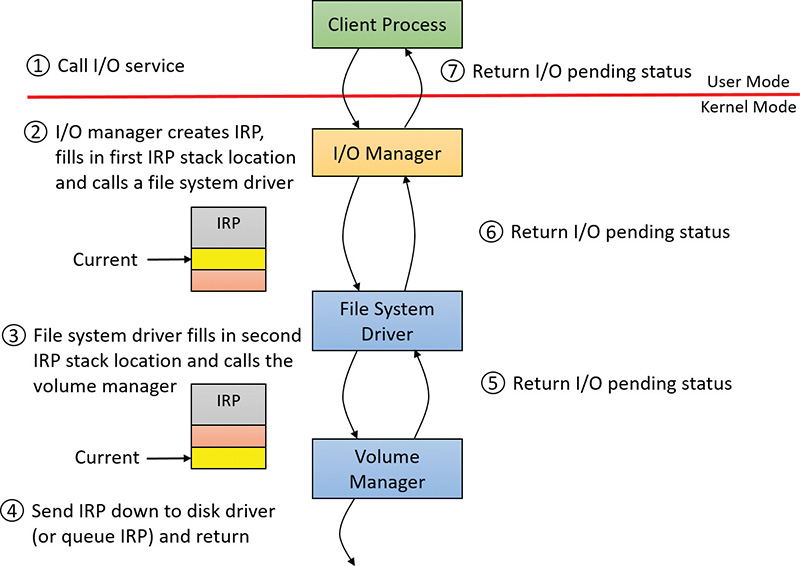

The operating system abstracts all I/O requests as operations on a virtual file because the I/O manager has no knowledge of anything but files, therefore making it the responsibility of the driver to translate file-oriented comments (open, close, read, write) into device-specific commands. This abstraction thereby generalizes an application’s interface to devices. User-mode applications call documented functions, which in turn call internal I/O system functions to read from a file, write to a file, and perform other operations. The I/O manager dynamically directs these virtual file requests to the appropriate device driver. Figure 6-3 illustrates the basic structure of a typical I/O read request flow. (Other types of I/O requests, such as write, are similar; they just use different APIs.)

The following sections look at these components more closely, covering the various types of device drivers, how they are structured, how they load and initialize, and how they process I/O requests. Then we’ll cover the operation and roles of the PnP manager and the power manager.

Interrupt Request Levels and Deferred Procedure Calls

Before we proceed, we must introduce two very important concepts of the Windows kernel that play an important role within the I/O system: Interrupt Request Levels (IRQL) and Deferred Procedure Calls (DPC). A thorough discussion of these concepts is reserved for Chapter 8 in Part 2, but we’ll provide enough information in this section to enable you to understand the mechanics of I/O processing that follow.

Interrupt Request Levels

The IRQL has two somewhat distinct meanings, but they converge in certain situations:

![]() An IRQL is a priority assigned to an interrupt source from a hardware device This number is set by the HAL (in conjunction with the interrupt controller to which devices that require interrupt servicing are connected).

An IRQL is a priority assigned to an interrupt source from a hardware device This number is set by the HAL (in conjunction with the interrupt controller to which devices that require interrupt servicing are connected).

![]() Each CPU has its own IRQL value It should be considered a register of the CPU (even though current CPUs do not implement it as such).

Each CPU has its own IRQL value It should be considered a register of the CPU (even though current CPUs do not implement it as such).

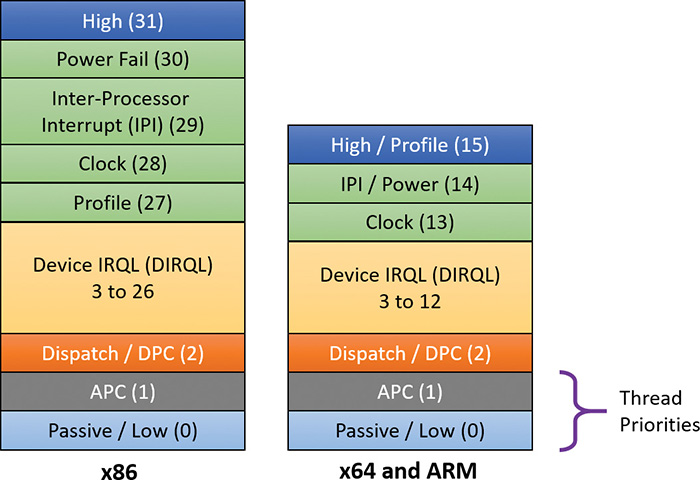

The fundamental rule of IRQLs is that lower IRQL code cannot interfere with higher IRQL code and vice versa—code with a higher IRQL can preempt code running at a lower IRQL. You’ll see examples of how this works in practice in a moment. A list of IRQLs for the Windows-supported architectures is shown in Figure 6-4. Note that IRQLs are not the same as thread priorities. In fact, thread priorities have meaning only when the IRQL is less than 2.

![]() Note

Note

IRQL is not the same as IRQ (interrupt request). IRQs are hardware lines connecting devices to an interrupt controller. See Chapter 8 in Part 2 for more on interrupts, IRQs, and IRQLs.

Normally, the IRQL of a processor is 0. This means “nothing special” is happening in that regard, and that the kernel’s scheduler that schedules threads based on priorities and so on works as described in Chapter 4, “Threads.” In user mode, the IRQL can only be 0. There is no way to raise IRQL from user mode. (That’s why user-mode documentation never mentions the IRQL concept at all; there would be no point.)

Kernel-mode code can raise and lower the current CPU IRQL with the KeRaiseIrql and KeLowerIrql functions. However, most of the time-specific functions are called with the IRQL raised to some expected level, as you’ll see shortly when we discuss a typical I/O processing by a driver.

The most important IRQLs for this I/O-related discussions are the following:

![]() Passive(0) This is defined by the

Passive(0) This is defined by the PASSIVE_LEVEL macro in the WDK header wdm.h. It is the normal IRQL where the kernel scheduler is working normally, as described at length in Chapter 4.

![]() Dispatch/DPC (2) (

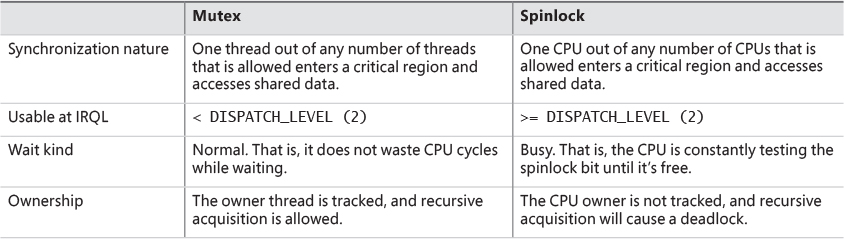

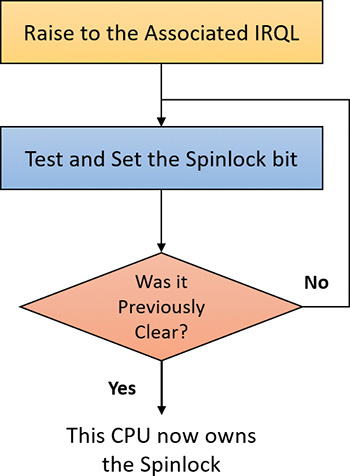

Dispatch/DPC (2) (DISPATCH_LEVEL) This is the IRQL the kernel’s scheduler works at. This means if a thread raises the current IRQL to 2 (or higher), the thread has essentially an infinite quantum and will not be preempted by another thread. Effectively, the scheduler cannot wake up on the current CPU until the IRQL drops below 2. This implies a few things:

• With the IRQL at level 2 or above, any waiting on kernel dispatcher objects (such as mutexes, semaphores, and events) would crash the system. This is because waiting implies that the thread might enter a wait state and another should be scheduled on the same CPU. However, because the scheduler is not around at this level, this cannot happen; instead, the system will bug-check (the only exception is if the wait timeout is zero, meaning no waiting is requested, just getting back the signaled state of the object).

• No page faults can be handled. This is because a page fault would require a context switch to one of the modified page writers. However, context switches are not allowed, so the system would crash. This means code running at IRQL 2 or above can access only non-paged memory—typically memory allocated from non-paged pool, which by definition is always resident in physical memory.

![]() Device IRQL (3–26 on x86; 3–12 on x64 and ARM) (

Device IRQL (3–26 on x86; 3–12 on x64 and ARM) (DIRQL) These are the levels assigned to hardware interrupts. When an interrupt arrives, the kernel’s trap dispatcher calls the appropriate interrupt service routine (ISR) and raises its IRQL to that of the associated interrupt. Because this value is always higher than DISPATCH_LEVEL (2), all rules associated with IRQL 2 apply for DIRQL as well.

Running at a particular IRQL masks interrupts with that and lower IRQLs. For example, an ISR running with IRQL of 8 would not let any code interfere (on that CPU) with IRQL of 7 or lower. Specifically, no user mode code is able to run because it always runs at IRQL 0. This implies that running in high IRQL is not desirable in the general case; there are a few specific scenarios (which we’ll look at in this chapter) where this makes sense and is in fact required for normal system operation.

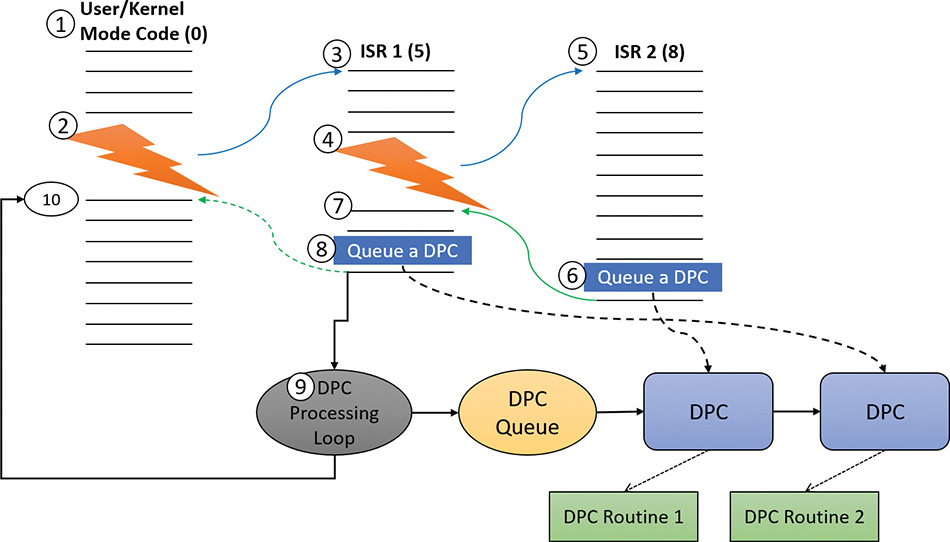

Deferred Procedure Calls

A Deferred Procedure Call (DPC) is an object that encapsulates calling a function at IRQL DPC_LEVEL (2). DPCs exist primarily for post-interrupt processing because running at DIRQL masks (and thus delays) other interrupts waiting to be serviced. A typical ISR would do the minimum work possible, mostly reading the state of the device and telling it to stop its interrupt signal and then deferring further processing to a lower IRQL (2) by requesting a DPC. The term Deferred means the DPC will not execute immediately—it can’t because the current IRQL is higher than 2. However, when the ISR returns, if there are no pending interrupts waiting to be serviced, the CPU IRQL will drop to 2 and it will execute the DPCs that have accumulated (maybe just one). Figure 6-5 shows a simplified example of the sequence of events that may occur when interrupts from hardware devices (which are asynchronous in nature, meaning they can arrive at any time) occur while code executes normally at IRQL 0 on some CPU.

Here is a rundown of the sequence of events shown in Figure 6-5:

1. Some user-mode or kernel-mode code is executing while the CPU is at IRQL 0, which is the case most of the time.

2. A hardware interrupt arrives with an IRQL of 5 (remember that Device IRQLs have a minimum value of 3). Because 5 is greater than zero (the current IRQL), the CPU state is saved, the IRQL is raised to 5, and the ISR associated with that interrupt is called. Note that there is no context switch; it’s the same thread that now happens to execute the ISR code. (If the thread was in user mode, it switches to kernel mode whenever an interrupt arrives.)

3. ISR 1 starts executing while the CPU IRQL is 5. At this point, any interrupt with IRQL 5 or lower cannot interrupt.

4. Suppose another interrupt arrives with an IRQL of 8. Assume the system decides that the same CPU should handle it. Because 8 is greater than 5, the code is interrupted again, the CPU state is saved, the IRQL is raised to 8, and the CPU jumps to ISR 2. Note again that it’s the same thread. No context switch can happen because the thread scheduler cannot wake up if the IRQL is 2 or higher.

5. ISR 2 is executing. Before it’s done, ISR 2 would like to do some more processing at a lower IRQL so that interrupts with IRQLs less than 8 could be services as well.

6. As its final act, ISR 2 inserts a DPC initialized properly to point to a driver routine to do any post processing after the interrupt is dismissed by calling the KeInsertQueueDpc function. (We’ll discuss what this post-processing typically includes in the next section.) Then the ISR returns, restoring the CPU state saved before entering ISR 2.

7. At this point, the IRQL drops to its previous level (5) and the CPU continues execution of ISR 1 that was interrupted before.

8. Just before ISR 1 finishes, it queues a DPC of its own to do its required post-processing. These DPCs are collected in a DPC queue that has not been examined yet. Then ISR 1 returns, restoring the CPU state saved before ISR 1 started execution.

9. At this point, the IRQL would want to drop to the old value of zero before all the interrupt handling began. However, the kernel notices that there are DPCs pending and so drops the IRQL to level 2 (DPC_LEVEL) and enters a DPC processing loop that iterates over the accumulated DPCs and calls each DPC routine in sequence. When the DPC queue is empty, DPC processing ends.

10. Finally, the IRQL can drop back to zero, restore the state of the CPU again, and resume execution of the original user or kernel code that got interrupted in the first place. Again, notice that all the processing described was done by the same thread (whichever one that may be). This fact implies that ISRs and DPC routines should not rely on any particular thread (and hence part of a particular process) to execute their code. It could be any thread, the significance of which will be discussed in the next section.

The preceding description is a bit simplified. It doesn’t mention DPC importance, other CPUs that may handle DPCs for quicker DPC processing, and more. These details are not important for the discussion in this chapter. However, they are described fully in Chapter 8 in Part 2.

Device drivers

To integrate with the I/O manager and other I/O system components, a device driver must conform to implementation guidelines specific to the type of device it manages and the role it plays in managing the device. This section discusses the types of device drivers Windows supports as well as the internal structure of a device driver.

![]() Note

Note

Most kernel-mode device drivers are written in C. Starting with the Windows Driver Kit 8.0, drivers can also be safely written in C++ due to specific support for kernel-mode C++ in the new compilers. Use of assembly language is highly discouraged because of the complexity it introduces and its effect of making a driver difficult to port between the hardware architectures supported by Windows (x86, x64, and ARM).

Types of device drivers

Windows supports a wide range of device-driver types and programming environments. Even within a particular type of device driver, programming environments can differ depending on the specific type of device for which a driver is intended.

The broadest classification of a driver is whether it is a user-mode or kernel-mode driver. Windows supports a couple of types of user-mode drivers:

![]() Windows subsystem printer drivers These translate device-independent graphics requests to printer-specific commands. These commands are then typically forwarded to a kernel-mode port driver such as the universal serial bus (USB) printer port driver (Usbprint.sys).

Windows subsystem printer drivers These translate device-independent graphics requests to printer-specific commands. These commands are then typically forwarded to a kernel-mode port driver such as the universal serial bus (USB) printer port driver (Usbprint.sys).

![]() User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF) drivers These are hardware device drivers that run in user mode. They communicate to the kernel-mode UMDF support library through advanced local procedure calls (ALPC). See the “User-Mode Driver Framework” section later in this chapter for more information.

User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF) drivers These are hardware device drivers that run in user mode. They communicate to the kernel-mode UMDF support library through advanced local procedure calls (ALPC). See the “User-Mode Driver Framework” section later in this chapter for more information.

In this chapter, the focus is on kernel-mode device drivers. There are many types of kernel-mode drivers, which can be divided into the following basic categories:

![]() File-system drivers These accept I/O requests to files and satisfy the requests by issuing their own more explicit requests to mass storage or network device drivers.

File-system drivers These accept I/O requests to files and satisfy the requests by issuing their own more explicit requests to mass storage or network device drivers.

![]() Plug and Play drivers These work with hardware and integrate with the Windows power manager and PnP manager. They include drivers for mass storage devices, video adapters, input devices, and network adapters.

Plug and Play drivers These work with hardware and integrate with the Windows power manager and PnP manager. They include drivers for mass storage devices, video adapters, input devices, and network adapters.

![]() Non–Plug and Play drivers These include kernel extensions, which are drivers or modules that extend the functionality of the system. They do not typically integrate with the PnP manager or power manager because they usually do not manage an actual piece of hardware. Examples include network API and protocol drivers. The Sysinternals tool Process Monitor has a driver, and is an example of a non-PnP driver.

Non–Plug and Play drivers These include kernel extensions, which are drivers or modules that extend the functionality of the system. They do not typically integrate with the PnP manager or power manager because they usually do not manage an actual piece of hardware. Examples include network API and protocol drivers. The Sysinternals tool Process Monitor has a driver, and is an example of a non-PnP driver.

Within the category of kernel-mode drivers are further classifications based on the driver model to which the driver adheres and its role in servicing device requests.

WDM drivers

WDM drivers are device drivers that adhere to the Windows Driver Model (WDM). WDM includes support for Windows power management, Plug and Play, and WMI, and most Plug and Play drivers adhere to WDM. There are three types of WDM drivers:

![]() Bus drivers These manage a logical or physical bus. Examples of buses include PCMCIA, PCI, USB, and IEEE 1394. A bus driver is responsible for detecting and informing the PnP manager of devices attached to the bus it controls and for managing the power setting of the bus. These are typically provided by Microsoft out of the box.

Bus drivers These manage a logical or physical bus. Examples of buses include PCMCIA, PCI, USB, and IEEE 1394. A bus driver is responsible for detecting and informing the PnP manager of devices attached to the bus it controls and for managing the power setting of the bus. These are typically provided by Microsoft out of the box.

![]() Function drivers These manage a particular type of device. Bus drivers present devices to function drivers via the PnP manager. The function driver is the driver that exports the operational interface of the device to the operating system. In general, it’s the driver with the most knowledge about the operation of the device.

Function drivers These manage a particular type of device. Bus drivers present devices to function drivers via the PnP manager. The function driver is the driver that exports the operational interface of the device to the operating system. In general, it’s the driver with the most knowledge about the operation of the device.

![]() Filter drivers These logically layer either above function drivers (these are called upper filters or function filters) or above the bus driver (these are called lower filters or bus filters), augmenting or changing the behavior of a device or another driver. For example, a keyboard-capture utility could be implemented with a keyboard filter driver that layers above the keyboard function driver.

Filter drivers These logically layer either above function drivers (these are called upper filters or function filters) or above the bus driver (these are called lower filters or bus filters), augmenting or changing the behavior of a device or another driver. For example, a keyboard-capture utility could be implemented with a keyboard filter driver that layers above the keyboard function driver.

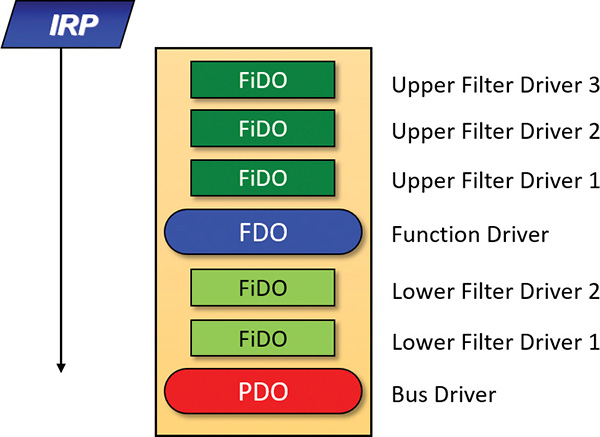

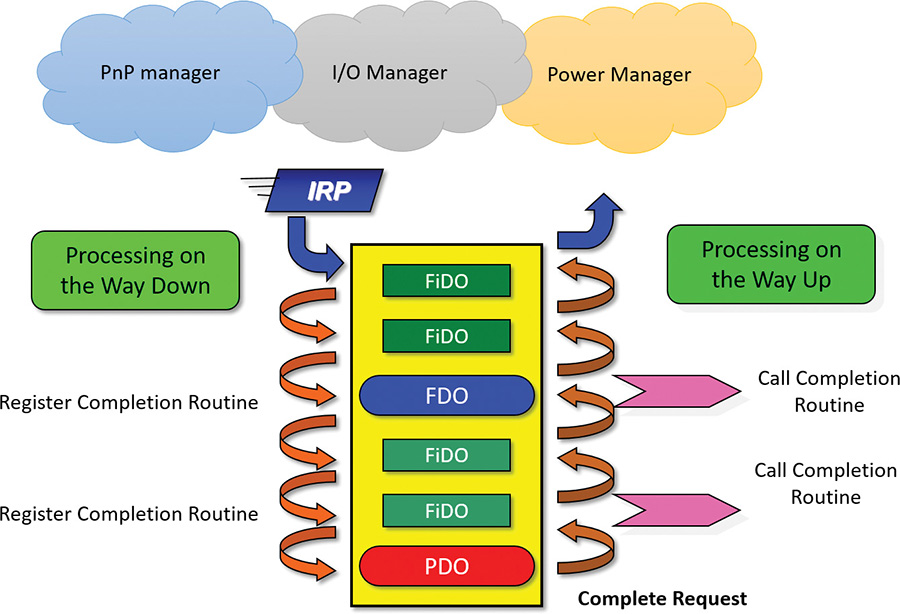

Figure 6-6 shows a device node (also called a devnode) with a bus driver that creates a physical device object (PDO), lower filters, a function driver that creates a functional device object (FDO), and upper filters. The only required layers are the PDO and FDO. The various filters may or may not exist.

In WDM, no one driver is responsible for controlling all aspects of a particular device. The bus driver is responsible for detecting bus membership changes (device addition or removal), assisting the PnP manager in enumerating the devices on the bus, accessing bus-specific configuration registers, and, in some cases, controlling power to devices on the bus. The function driver is generally the only driver that accesses the device’s hardware. The exact manner in which these devices came to be is described in “The Plug and Play manager” section later in this chapter.

Layered drivers

Support for an individual piece of hardware is often divided among several drivers, each providing a part of the functionality required to make the device work properly. In addition to WDM bus drivers, function drivers, and filter drivers, hardware support might be split between the following components:

![]() Class drivers These implement the I/O processing for a particular class of devices, such as disk, keyboard, or CD-ROM, where the hardware interfaces have been standardized so one driver can serve devices from a wide variety of manufacturers.

Class drivers These implement the I/O processing for a particular class of devices, such as disk, keyboard, or CD-ROM, where the hardware interfaces have been standardized so one driver can serve devices from a wide variety of manufacturers.

![]() Miniclass drivers These implement I/O processing that is vendor-defined for a particular class of devices. For example, although Microsoft has written a standardized battery class driver, both uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) and laptop batteries have highly specific interfaces that differ wildly between manufacturers, such that a miniclass is required from the vendor. Miniclass drivers are essentially kernel-mode DLLs and do not perform IRP processing directly. Instead, the class driver calls into them and they import functions from the class driver.

Miniclass drivers These implement I/O processing that is vendor-defined for a particular class of devices. For example, although Microsoft has written a standardized battery class driver, both uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) and laptop batteries have highly specific interfaces that differ wildly between manufacturers, such that a miniclass is required from the vendor. Miniclass drivers are essentially kernel-mode DLLs and do not perform IRP processing directly. Instead, the class driver calls into them and they import functions from the class driver.

![]() Port drivers These implement the processing of an I/O request specific to a type of I/O port, such as SATA, and are implemented as kernel-mode libraries of functions rather than actual device drivers. Port drivers are almost always written by Microsoft because the interfaces are typically standardized in such a way that different vendors can still share the same port driver. However, in certain cases, third parties may need to write their own for specialized hardware. In some cases, the concept of I/O port extends to cover logical ports as well. For example, Network Driver Interface Specification (NDIS) is the network “port” driver.

Port drivers These implement the processing of an I/O request specific to a type of I/O port, such as SATA, and are implemented as kernel-mode libraries of functions rather than actual device drivers. Port drivers are almost always written by Microsoft because the interfaces are typically standardized in such a way that different vendors can still share the same port driver. However, in certain cases, third parties may need to write their own for specialized hardware. In some cases, the concept of I/O port extends to cover logical ports as well. For example, Network Driver Interface Specification (NDIS) is the network “port” driver.

![]() Miniport drivers These map a generic I/O request to a type of port into an adapter type, such as a specific network adapter. Miniport drivers are actual device drivers that import the functions supplied by a port driver. Miniport drivers are written by third parties, and they provide the interface for the port driver. Like miniclass drivers, they are kernel-mode DLLs and do not perform IRP processing directly.

Miniport drivers These map a generic I/O request to a type of port into an adapter type, such as a specific network adapter. Miniport drivers are actual device drivers that import the functions supplied by a port driver. Miniport drivers are written by third parties, and they provide the interface for the port driver. Like miniclass drivers, they are kernel-mode DLLs and do not perform IRP processing directly.

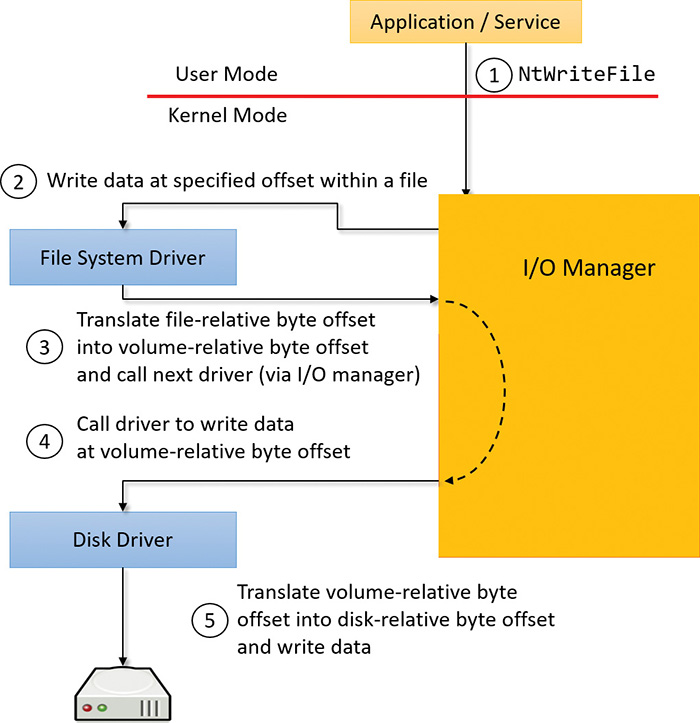

Figure 6-7 shows a simplified example for illustrative purposes that will help demonstrate how device drivers and layering work at a high level. As you can see, a file-system driver accepts a request to write data to a certain location within a particular file. It translates the request into a request to write a certain number of bytes to the disk at a particular (that is, the logical) location. It then passes this request (via the I/O manager) to a simple disk driver. The disk driver, in turn, translates the request into a physical location on the disk and communicates with the disk to write the data.

This figure illustrates the division of labor between two layered drivers. The I/O manager receives a write request that is relative to the beginning of a particular file. The I/O manager passes the request to the file-system driver, which translates the write operation from a file-relative operation to a starting location (a sector boundary on the disk) and a number of bytes to write. The file-system driver calls the I/O manager to pass the request to the disk driver, which translates the request to a physical disk location and transfers the data.

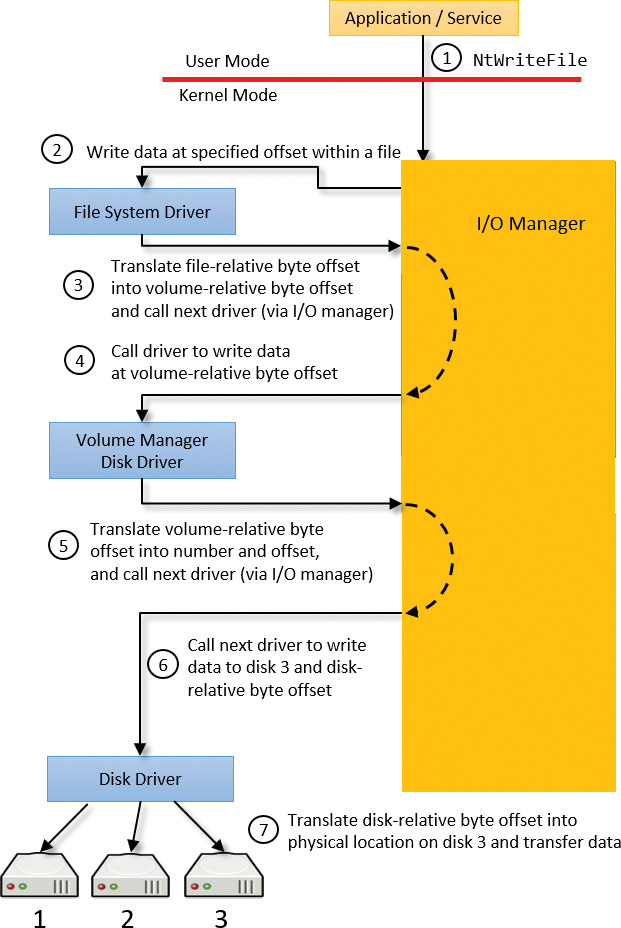

Because all drivers—both device drivers and file-system drivers—present the same framework to the operating system, another driver can easily be inserted into the hierarchy without altering the existing drivers or the I/O system. For example, several disks can be made to seem like a very large single disk by adding a driver. This logical volume manager driver is located between the file system and the disk drivers, as shown in the conceptual simplified architectural diagram presented in Figure 6-8. (For the actual storage driver stack diagram as well as volume manager drivers, see Chapter 12, “Storage management” in Part 2.)

Structure of a driver

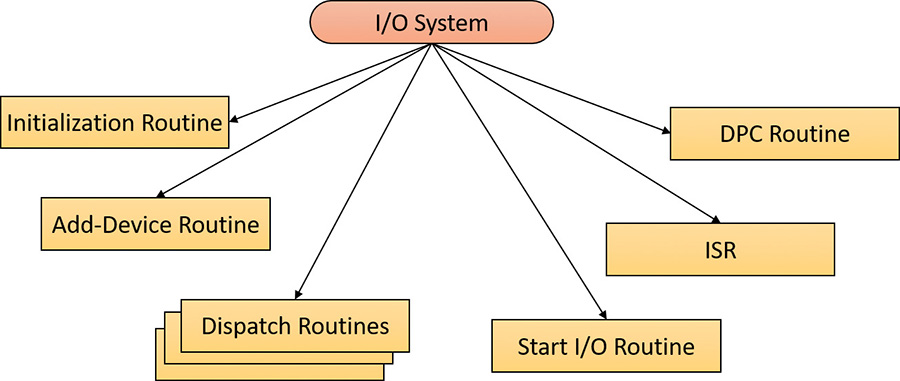

The I/O system drives the execution of device drivers. Device drivers consist of a set of routines that are called to process the various stages of an I/O request. Figure 6-9 illustrates the key driver-function routines, which are described next.

![]() An initialization routine The I/O manager executes a driver’s initialization routine, which is set by the WDK to

An initialization routine The I/O manager executes a driver’s initialization routine, which is set by the WDK to GSDriverEntry when it loads the driver into the operating system. GSDriverEntry initializes the compiler’s protection against stack-overflow errors (called a cookie) and then calls DriverEntry, which is what the driver writer must implement. The routine fills in system data structures to register the rest of the driver’s routines with the I/O manager and performs any necessary global driver initialization.

![]() An add-device routine A driver that supports Plug and Play implements an add-device routine. The PnP manager sends a notification to the driver via this routine whenever a device for which the driver is responsible is detected. In this routine, a driver typically creates a device object (described later in this chapter) to represent the device.

An add-device routine A driver that supports Plug and Play implements an add-device routine. The PnP manager sends a notification to the driver via this routine whenever a device for which the driver is responsible is detected. In this routine, a driver typically creates a device object (described later in this chapter) to represent the device.

![]() A set of dispatch routines Dispatch routines are the main entry points that a device driver provides. Some examples are open, close, read, write, and Plug and Play. When called on to perform an I/O operation, the I/O manager generates an IRP and calls a driver through one of the driver’s dispatch routines.

A set of dispatch routines Dispatch routines are the main entry points that a device driver provides. Some examples are open, close, read, write, and Plug and Play. When called on to perform an I/O operation, the I/O manager generates an IRP and calls a driver through one of the driver’s dispatch routines.

![]() A start I/O routine A driver can use a start I/O routine to initiate a data transfer to or from a device. This routine is defined only in drivers that rely on the I/O manager to queue their incoming I/O requests. The I/O manager serializes IRPs for a driver by ensuring that the driver processes only one IRP at a time. Drivers can process multiple IRPs concurrently, but serialization is usually required for most devices because they cannot concurrently handle multiple I/O requests.

A start I/O routine A driver can use a start I/O routine to initiate a data transfer to or from a device. This routine is defined only in drivers that rely on the I/O manager to queue their incoming I/O requests. The I/O manager serializes IRPs for a driver by ensuring that the driver processes only one IRP at a time. Drivers can process multiple IRPs concurrently, but serialization is usually required for most devices because they cannot concurrently handle multiple I/O requests.

![]() An interrupt service routine (ISR) When a device interrupts, the kernel’s interrupt dispatcher transfers control to this routine. In the Windows I/O model, ISRs run at device interrupt request level (DIRQL), so they perform as little work as possible to avoid blocking lower IRQL interrupts (as discussed in the previous section). An ISR usually queues a DPC, which runs at a lower IRQL (DPC/dispatch level) to execute the remainder of interrupt processing. Only drivers for interrupt-driven devices have ISRs; a file-system driver, for example, doesn’t have one.

An interrupt service routine (ISR) When a device interrupts, the kernel’s interrupt dispatcher transfers control to this routine. In the Windows I/O model, ISRs run at device interrupt request level (DIRQL), so they perform as little work as possible to avoid blocking lower IRQL interrupts (as discussed in the previous section). An ISR usually queues a DPC, which runs at a lower IRQL (DPC/dispatch level) to execute the remainder of interrupt processing. Only drivers for interrupt-driven devices have ISRs; a file-system driver, for example, doesn’t have one.

![]() An interrupt-servicing DPC routine A DPC routine performs most of the work involved in handling a device interrupt after the ISR executes. The DPC routine executes at IRQL 2, which is a “compromise” between the high DIRQL and the low passive level (0). A typical DPC routine initiates I/O completion and starts the next queued I/O operation on a device.

An interrupt-servicing DPC routine A DPC routine performs most of the work involved in handling a device interrupt after the ISR executes. The DPC routine executes at IRQL 2, which is a “compromise” between the high DIRQL and the low passive level (0). A typical DPC routine initiates I/O completion and starts the next queued I/O operation on a device.

Although the following routines aren’t shown in Figure 6-9, they’re found in many types of device drivers:

![]() One or more I/O completion routines A layered driver might have I/O completion routines that notify it when a lower-level driver finishes processing an IRP. For example, the I/O manager calls a file-system driver’s I/O completion routine after a device driver finishes transferring data to or from a file. The completion routine notifies the file-system driver about the operation’s success, failure, or cancellation, and allows the file-system driver to perform cleanup operations.

One or more I/O completion routines A layered driver might have I/O completion routines that notify it when a lower-level driver finishes processing an IRP. For example, the I/O manager calls a file-system driver’s I/O completion routine after a device driver finishes transferring data to or from a file. The completion routine notifies the file-system driver about the operation’s success, failure, or cancellation, and allows the file-system driver to perform cleanup operations.

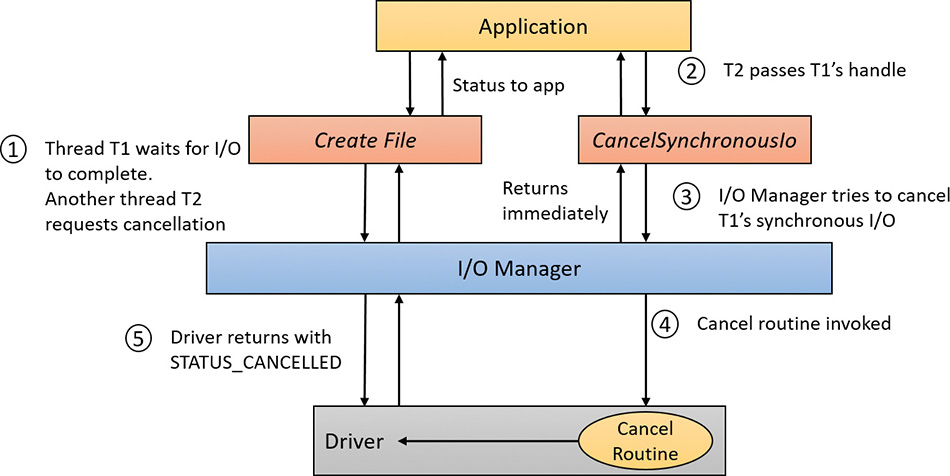

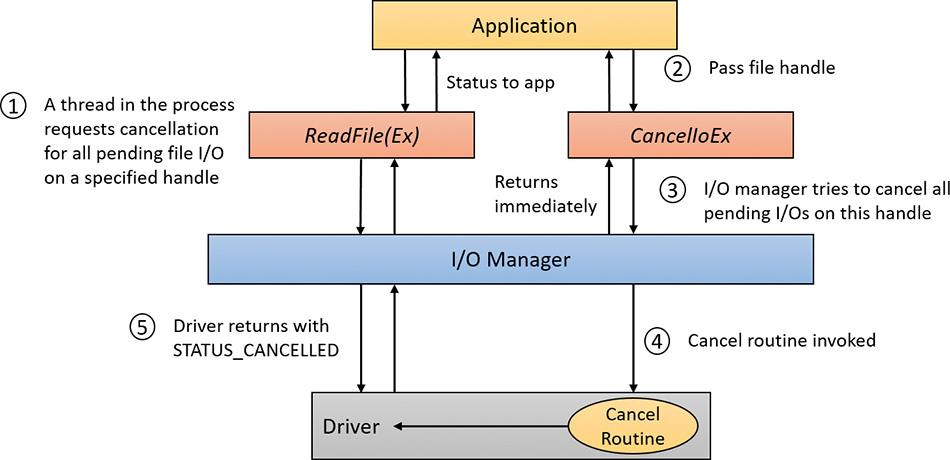

![]() A cancel I/O routine If an I/O operation can be canceled, a driver can define one or more cancel I/O routines. When the driver receives an IRP for an I/O request that can be canceled, it assigns a cancel routine to the IRP. As the IRP goes through various stages of processing, this routine can change or outright disappear if the current operation is not cancellable. If a thread that issues an I/O request exits before the request is completed or the operation is cancelled (for example, with the

A cancel I/O routine If an I/O operation can be canceled, a driver can define one or more cancel I/O routines. When the driver receives an IRP for an I/O request that can be canceled, it assigns a cancel routine to the IRP. As the IRP goes through various stages of processing, this routine can change or outright disappear if the current operation is not cancellable. If a thread that issues an I/O request exits before the request is completed or the operation is cancelled (for example, with the CancelIo or CancelIoEx Windows functions), the I/O manager executes the IRP’s cancel routine if one is assigned to it. A cancel routine is responsible for performing whatever steps are necessary to release any resources acquired during the processing that has already taken place for the IRP as well as for completing the IRP with a canceled status.

![]() Fast-dispatch routines Drivers that make use of the cache manager, such as file-system drivers, typically provide these routines to allow the kernel to bypass typical I/O processing when accessing the driver. (See Chapter 14, “Cache manager,” in Part 2, for more information on the cache manager.) For example, operations such as reading or writing can be quickly performed by accessing the cached data directly instead of taking the I/O manager’s usual path that generates discrete I/O operations. Fast dispatch routines are also used as a mechanism for callbacks from the memory manager and cache manager to file-system drivers. For instance, when creating a section, the memory manager calls back into the file-system driver to acquire the file exclusively.

Fast-dispatch routines Drivers that make use of the cache manager, such as file-system drivers, typically provide these routines to allow the kernel to bypass typical I/O processing when accessing the driver. (See Chapter 14, “Cache manager,” in Part 2, for more information on the cache manager.) For example, operations such as reading or writing can be quickly performed by accessing the cached data directly instead of taking the I/O manager’s usual path that generates discrete I/O operations. Fast dispatch routines are also used as a mechanism for callbacks from the memory manager and cache manager to file-system drivers. For instance, when creating a section, the memory manager calls back into the file-system driver to acquire the file exclusively.

![]() An unload routine An unload routine releases any system resources a driver is using so that the I/O manager can remove the driver from memory. Any resources acquired in the initialization routine (

An unload routine An unload routine releases any system resources a driver is using so that the I/O manager can remove the driver from memory. Any resources acquired in the initialization routine (DriverEntry) are usually released in the unload routine. A driver can be loaded and unloaded while the system is running if the driver supports it, but the unload routine will be called only after all file handles to the device are closed.

![]() A system shutdown notification routine This routine allows driver cleanup on system shutdown.

A system shutdown notification routine This routine allows driver cleanup on system shutdown.

![]() Error-logging routines When unexpected errors occur (for example, when a disk block goes bad), a driver’s error-logging routines note the occurrence and notify the I/O manager. The I/O manager then writes this information to an error log file.

Error-logging routines When unexpected errors occur (for example, when a disk block goes bad), a driver’s error-logging routines note the occurrence and notify the I/O manager. The I/O manager then writes this information to an error log file.

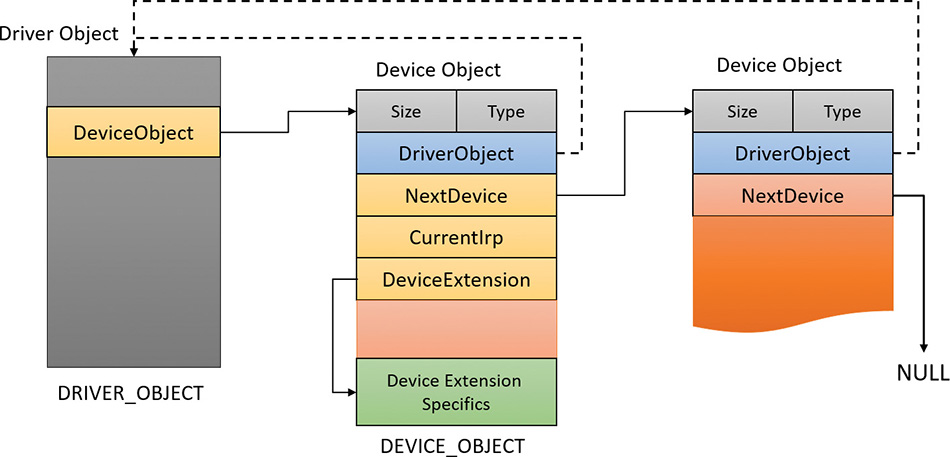

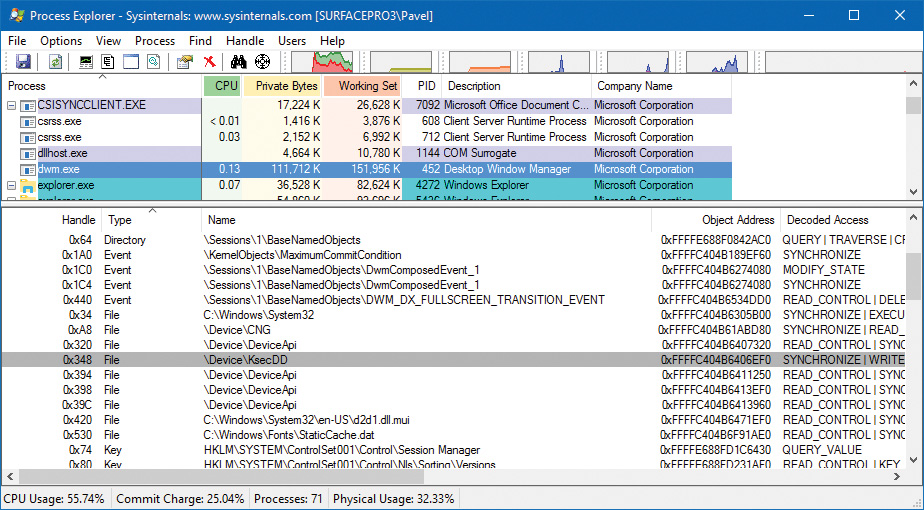

Driver objects and device objects

When a thread opens a handle to a file object (described in the “I/O processing” section later in this chapter), the I/O manager must determine from the file object’s name which driver it should call to process the request. Furthermore, the I/O manager must be able to locate this information the next time a thread uses the same file handle. The following system objects fill this need:

![]() A driver object This represents an individual driver in the system (

A driver object This represents an individual driver in the system (DRIVER_OBJECT structure). The I/O manager obtains the address of each of the driver’s dispatch routines (entry points) from the driver object.

![]() A device object This represents a physical or logical device on the system and describes its characteristics (

A device object This represents a physical or logical device on the system and describes its characteristics (DEVICE_OBJECT structure), such as the alignment it requires for buffers and the location of its device queue to hold incoming IRPs. It is the target for all I/O operations because this object is what the handle communicates with.

The I/O manager creates a driver object when a driver is loaded into the system. It then calls the driver’s initialization routine (DriverEntry), which fills in the object attributes with the driver’s entry points.

At any time after loading, a driver creates device objects to represent logical or physical devices—or even a logical interface or endpoint to the driver—by calling IoCreateDevice or IoCreateDevice-Secure. However, most Plug and Play drivers create devices in their add-device routine when the PnP manager informs them of the presence of a device for them to manage. Non–Plug and Play drivers, on the other hand, usually create device objects when the I/O manager invokes their initialization routine. The I/O manager unloads a driver when the driver’s last device object has been deleted and no references to the driver remain.

The relationship between a driver object and its device objects is shown in Figure 6-10.

A driver object holds a pointer to its first device object in the DeviceObject member. The second device object is pointed to by the NextDevice member of DEVICE_OBJECT until the last one points to NULL. Each device object points back to its driver object with the DriverObject member. All the arrows shown in Figure 6-10 are built by the device-creation functions (IoCreateDevice or IoCreateDevice-Secure). The DeviceExtension pointer shown is a way a driver can allocate an extra piece of memory that is attached to each device object it manages.

![]() Note

Note

It’s important to distinguish driver objects from device objects. A driver object represents the behavior of a driver, while individual device objects represent communication endpoints. For example, on a system with four serial ports, there would be one driver object (and one driver binary) but four instances of device objects, each representing a single serial port, that can be opened individually with no effect on the other serial ports. For hardware devices, each device also represents a distinct set of hardware resources, such as I/O ports, memory-mapped I/O, and interrupt line. Windows is device-centric, rather than driver-centric.

When a driver creates a device object, the driver can optionally assign the device a name. A name places the device object in the object manager namespace. A driver can either explicitly define a name or let the I/O manager auto-generate one. By convention, device objects are placed in the \Device directory in the namespace, which is inaccessible by applications using the Windows API.

Some drivers place device objects in directories other than \Device. For example, the IDE driver creates the device objects that represent IDE ports and channels in the \Device\Ide directory. See Chapter 12 in Part 2 for a description of storage architecture, including the way storage drivers use device objects.

If a driver needs to make it possible for applications to open the device object, it must create a symbolic link in the \GLOBAL?? directory to the device object’s name in the \Device directory. (The IoCreateSymbolicLink function accomplishes this.) Non–Plug and Play and file-system drivers typically create a symbolic link with a well-known name (for example, \Device\HarddiskVolume2). Because well-known names don’t work well in an environment in which hardware appears and disappears dynamically, PnP drivers expose one or more interfaces by calling the IoRegisterDeviceInterface function, specifying a globally unique identifier (GUID) that represents the type of functionality exposed. GUIDs are 128-bit values that can be generated by using tools such as uuidgen and guidgen, which are included with the WDK and the Windows SDK. Given the range of values that 128 bits represents (and the formula used to generate them), it’s statistically almost certain that each GUID generated will be forever and globally unique.

IoRegisterDeviceInterface generates the symbolic link associated with a device instance. However, a driver must call IoSetDeviceInterfaceState to enable the interface to the device before the I/O manager actually creates the link. Drivers usually do this when the PnP manager starts the device by sending the driver a start-device IRP—in this case, IRP_MJ_PNP (major function code) with IRP_MN_START_DEVICE (minor function code). IRPs are discussed in the “I/O request packets” section later in this chapter.

An application that wants to open a device object whose interfaces are represented with a GUID can call Plug and Play setup functions in user space, such as SetupDiEnumDeviceInterfaces, to enumerate the interfaces present for a particular GUID and to obtain the names of the symbolic links it can use to open the device objects. For each device reported by SetupDiEnumDeviceInterfaces, the application executes SetupDiGetDeviceInterfaceDetail to obtain additional information about the device, such as its auto-generated name. After obtaining a device’s name from SetupDiGetDeviceInterface- Detail, the application can execute the Windows function CreateFile or CreateFile2 to open the device and obtain a handle.

As Figure 6-10 illustrates, a device object points back to its driver object, which is how the I/O manager knows which driver routine to call when it receives an I/O request. It uses the device object to find the driver object representing the driver that services the device. It then indexes into the driver object by using the function code supplied in the original request. Each function code corresponds to a driver entry point (called a dispatch routine).

A driver object often has multiple device objects associated with it. When a driver is unloaded from the system, the I/O manager uses the queue of device objects to determine which devices will be affected by the removal of the driver.

Using objects to record information about drivers means that the I/O manager doesn’t need to know details about individual drivers. The I/O manager merely follows a pointer to locate a driver, thereby providing a layer of portability and allowing new drivers to be loaded easily.

Opening devices

A file object is a kernel-mode data structure that represents a handle to a device. File objects clearly fit the criteria for objects in Windows: They are system resources that two or more user-mode processes can share; they can have names; they are protected by object-based security; and they support synchronization. Shared resources in the I/O system, like those in other components of the Windows executive, are manipulated as objects. (See Chapter 8 in Part 2 for more on object management.)

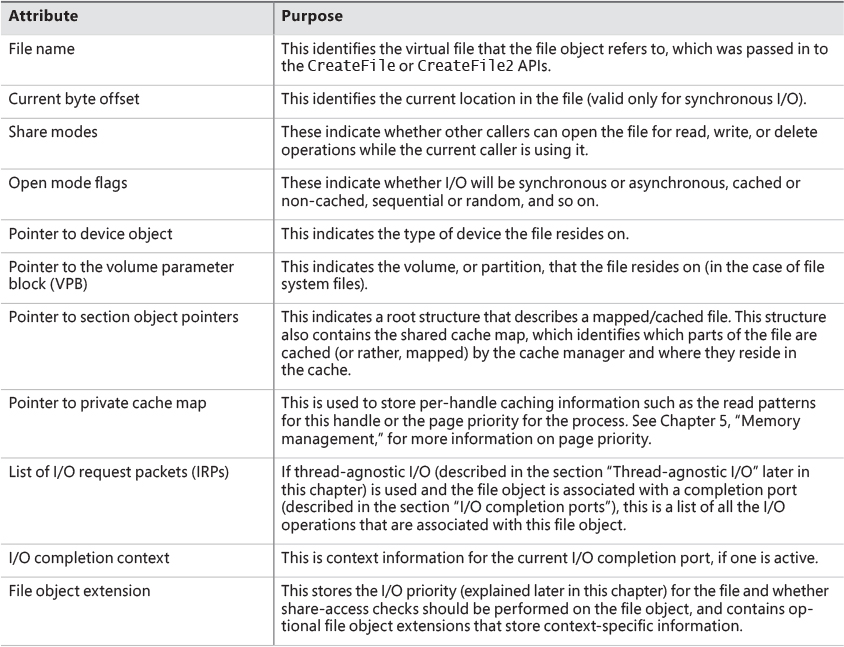

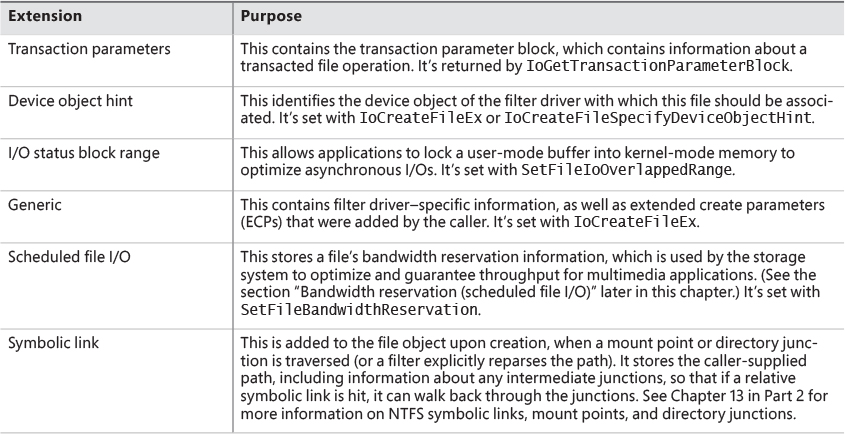

File objects provide a memory-based representation of resources that conform to an I/O-centric interface, in which they can be read from or written to. Table 6-1 lists some of the file object’s attributes. For specific field declarations and sizes, see the structure definition for FILE_OBJECT in wdm.h.

To maintain some level of opacity toward driver code that uses the file object, and to enable extending the file object functionality without enlarging the structure, the file object also contains an extension field, which allows for up to six different kinds of additional attributes, described in Table 6-2.

When a caller opens a file or a simple device, the I/O manager returns a handle to a file object. Before that happens, the driver responsible for the device in question is asked via its Create dispatch routine (IRP_MJ_CREATE) whether it’s OK to open the device and allow the driver to perform any initialization necessary if the open request is to succeed.

![]() Note

Note

File objects represent open instances of files, not files themselves. Unlike UNIX systems, which use vnodes, Windows does not define the representation of a file; Windows file-system drivers define their own representations.

Similar to executive objects, files are protected by a security descriptor that contains an access control list (ACL). The I/O manager consults the security subsystem to determine whether a file’s ACL allows the process to access the file in the way its thread is requesting. If it does, the object manager grants the access and associates the granted access rights with the file handle that it returns. If this thread or another thread in the process needs to perform additional operations not specified in the original request, the thread must open the same file again with a different request (or duplicate the handle with the requested access) to get another handle, which prompts another security check. (See Chapter 7 for more information about object protection.)

Because a file object is a memory-based representation of a shareable resource and not the resource itself, it’s different from other executive objects. A file object contains only data that is unique to an object handle, whereas the file itself contains the data or text to be shared. Each time a thread opens a file, a new file object is created with a new set of handle-specific attributes. For example, for files opened synchronously, the current byte offset attribute refers to the location in the file at which the next read or write operation using that handle will occur. Each handle to a file has a private byte offset even though the underlying file is shared. A file object is also unique to a process—except when a process duplicates a file handle to another process (by using the Windows DuplicateHandle function) or when a child process inherits a file handle from a parent process. In these situations, the two processes have separate handles that refer to the same file object.

Although a file handle is unique to a process, the underlying physical resource is not. Therefore, as with any shared resource, threads must synchronize their access to shareable resources such as files, file directories, and devices. If a thread is writing to a file, for example, it should specify exclusive write access when opening the file to prevent other threads from writing to the file at the same time. Alternatively, by using the Windows LockFile function, the thread could lock a portion of the file while writing to it when exclusive access is required.

When a file is opened, the file name includes the name of the device object on which the file resides. For example, the name \Device\HarddiskVolume1\Myfile.dat may refer to the file Myfile.dat on the C: volume. The substring \Device\HarddiskVolume1 is the name of the internal Windows device object representing that volume. When opening Myfile.dat, the I/O manager creates a file object and stores a pointer to the HarddiskVolume1 device object in the file object and then returns a file handle to the caller. Thereafter, when the caller uses the file handle, the I/O manager can find the HarddiskVolume1 device object directly.

Keep in mind that internal Windows device names can’t be used in Windows applications—instead, the device name must appear in a special directory in the object manager’s namespace, which is \GLOBAL??. This directory contains symbolic links to the real, internal Windows device names. As was described earlier, device drivers are responsible for creating links in this directory so that their devices will be accessible to Windows applications. You can examine or even change these links programmatically with the Windows QueryDosDevice and DefineDosDevice functions.

I/O processing

Now that we’ve covered the structure and types of drivers and the data structures that support them, let’s look at how I/O requests flow through the system. I/O requests pass through several predictable stages of processing. The stages vary depending on whether the request is destined for a device operated by a single-layered driver or for a device reached through a multilayered driver. Processing varies further depending on whether the caller specified synchronous or asynchronous I/O, so we’ll begin our discussion of I/O types with these two and then move on to others.

Types of I/O

Applications have several options for the I/O requests they issue. Furthermore, the I/O manager gives drivers the choice of implementing a shortcut I/O interface that can often mitigate IRP allocation for I/O processing. In this section, we’ll explain these options for I/O requests.

Synchronous and asynchronous I/O

Most I/O operations issued by applications are synchronous (which is the default). That is, the application thread waits while the device performs the data operation and returns a status code when the I/O is complete. The program can then continue and access the transferred data immediately. When used in their simplest form, the Windows ReadFile and WriteFile functions are executed synchronously. They complete the I/O operation before returning control to the caller.

Asynchronous I/O allows an application to issue multiple I/O requests and continue executing while the device performs the I/O operation. This type of I/O can improve an application’s throughput because it allows the application thread to continue with other work while an I/O operation is in progress. To use asynchronous I/O, you must specify the FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED flag when you call the Windows CreateFile or CreateFile2 functions. Of course, after issuing an asynchronous I/O operation, the thread must be careful not to access any data from the I/O operation until the device driver has finished the data operation. The thread must synchronize its execution with the completion of the I/O request by monitoring a handle of a synchronization object (whether that’s an event object, an I/O completion port, or the file object itself) that will be signaled when the I/O is complete.

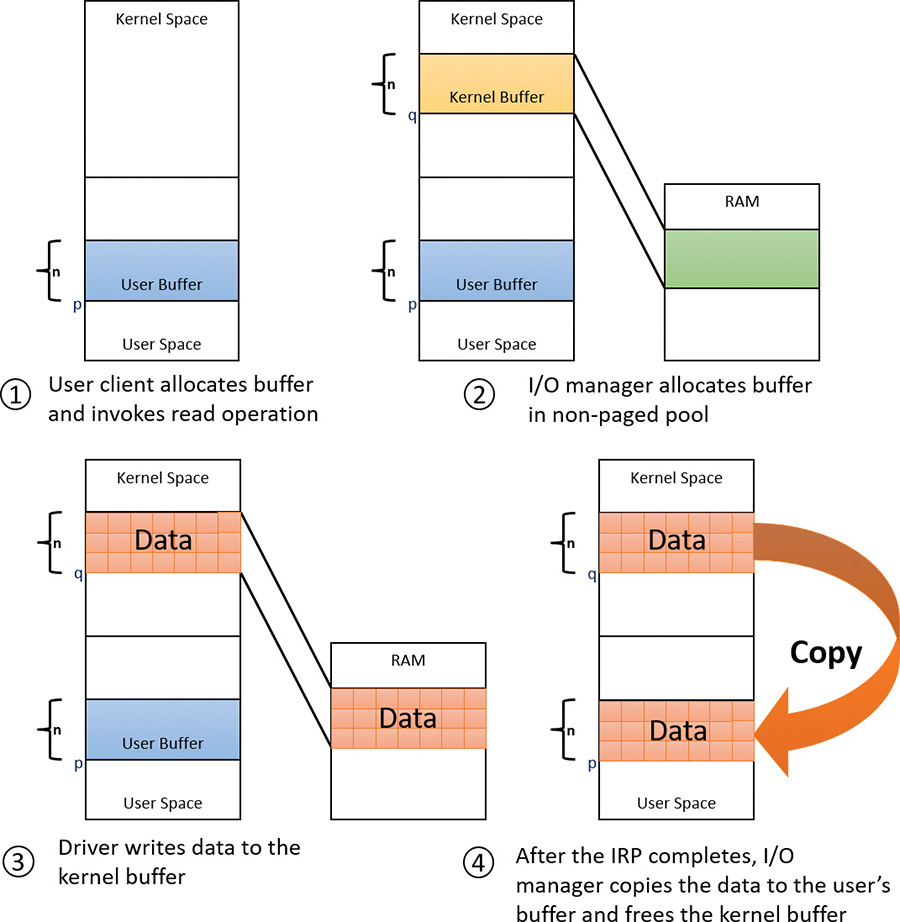

Regardless of the type of I/O request, I/O operations issued to a driver on behalf of the application are performed asynchronously. That is, once an I/O request has been initiated, the device driver must return to the I/O system as soon as possible. Whether or not the I/O system returns immediately to the caller depends on whether the handle was opened for synchronous or asynchronous I/O. Figure 6-3 illustrates the flow of control when a read operation is initiated. Notice that if a wait is done, which depends on the overlapped flag in the file object, it is done in kernel mode by the NtReadFile function.

You can test the status of a pending asynchronous I/O operation with the Windows HasOverlapped- IoCompleted macro or get more details with the GetOverlappedResult(Ex) functions. If you’re using I/O completion ports (described in the “I/O completion ports” section later in this chapter), you can use the GetQueuedCompletionStatus(Ex) function(s).

Fast I/O

Fast I/O is a special mechanism that allows the I/O system to bypass the generation of an IRP and instead go directly to the driver stack to complete an I/O request. This mechanism is used for optimizing certain I/O paths, which are somewhat slower when using IRPs. (Fast I/O is described in detail in Chapter 13 and Chapter 14 in Part 2.) A driver registers its fast I/O entry points by entering them in a structure pointed to by the PFAST_IO_DISPATCH pointer in its driver object.

Mapped-file I/O and file caching

Mapped-file I/O is an important feature of the I/O system—one that the I/O system and the memory manager produce jointly. (See Chapter 5 for details on how mapped files are implemented.) Mapped-file I/O refers to the ability to view a file residing on disk as part of a process’s virtual memory. A program can access the file as a large array without buffering data or performing disk I/O. The program accesses memory, and the memory manager uses its paging mechanism to load the correct page from the disk file. If the application writes to its virtual address space, the memory manager writes the changes back to the file as part of normal paging.

Mapped-file I/O is available in user mode through the Windows CreateFileMapping, MapViewOfFile, and related functions. Within the operating system, mapped-file I/O is used for important operations such as file caching and image activation (loading and running executable programs). The other major consumer of mapped-file I/O is the cache manager. File systems use the cache manager to map file data in virtual memory to provide better response time for I/O-bound programs. As the caller uses the file, the memory manager brings accessed pages into memory. Whereas most caching systems allocate a fixed number of bytes for caching files in memory, the Windows cache grows or shrinks depending on how much memory is available. This size variability is possible because the cache manager relies on the memory manager to automatically expand (or shrink) the size of the cache using the normal working set mechanisms explained in Chapter 5—in this case applied to the system working set. By taking advantage of the memory manager’s paging system, the cache manager avoids duplicating the work that the memory manager already performs. (The workings of the cache manager are explained in detail in Chapter 14 in Part 2.)

Scatter/gather I/O

Windows supports a special kind of high-performance I/O called scatter/gather, available via the Windows ReadFileScatter and WriteFileGather functions. These functions allow an application to issue a single read or write from more than one buffer in virtual memory to a contiguous area of a file on disk instead of issuing a separate I/O request for each buffer. To use scatter/gather I/O, the file must be opened for non-cached I/O, the user buffers being used must be page-aligned, and the I/Os must be asynchronous (overlapped). Furthermore, if the I/O is directed at a mass storage device, the I/O must be aligned on a device sector boundary and have a length that is a multiple of the sector size.

I/O request packets

An I/O request packet (IRP) is where the I/O system stores information it needs to process an I/O request. When a thread calls an I/O API, the I/O manager constructs an IRP to represent the operation as it progresses through the I/O system. If possible, the I/O manager allocates IRPs from one of three per-processor IRP non-paged look-aside lists:

![]() The small-IRP look-aside list This stores IRPs with one stack location. (IRP stack locations are described shortly.)

The small-IRP look-aside list This stores IRPs with one stack location. (IRP stack locations are described shortly.)

![]() The medium-IRP look-aside list This contains IRPs with four stack locations (which can also be used for IRPs that require only two or three stack locations).

The medium-IRP look-aside list This contains IRPs with four stack locations (which can also be used for IRPs that require only two or three stack locations).

![]() The large-IRP look-aside list This contains IRPs with more than four stack locations. By default, the system stores IRPs with 14 stack locations on the large-IRP look-aside list, but once per minute, the system adjusts the number of stack locations allocated and can increase it up to a maximum of 20, based on how many stack locations have been recently required.

The large-IRP look-aside list This contains IRPs with more than four stack locations. By default, the system stores IRPs with 14 stack locations on the large-IRP look-aside list, but once per minute, the system adjusts the number of stack locations allocated and can increase it up to a maximum of 20, based on how many stack locations have been recently required.

These lists are also backed by global look-aside lists as well, allowing efficient cross-CPU IRP flow. If an IRP requires more stack locations than are contained in the IRPs on the large-IRP look-aside list, the I/O manager allocates IRPs from non-paged pool. The I/O manager allocates IRPs with the IoAllocate-Irp function, which is also available for device-driver developers, because in some cases a driver may want to initiate an I/O request directly by creating and initializing its own IRPs. After allocating and initializing an IRP, the I/O manager stores a pointer to the caller’s file object in the IRP.

![]() Note

Note

If defined, the DWORD registry value LargeIrpStackLocations in the HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Session Manager\I/O System key specifies how many stack locations are contained in IRPs stored on the large-IRP look-aside list. Similarly, the MediumIrpStackLocations value in the same key can be used to change the size of IRP stack locations on the medium-IRP look-aside list.

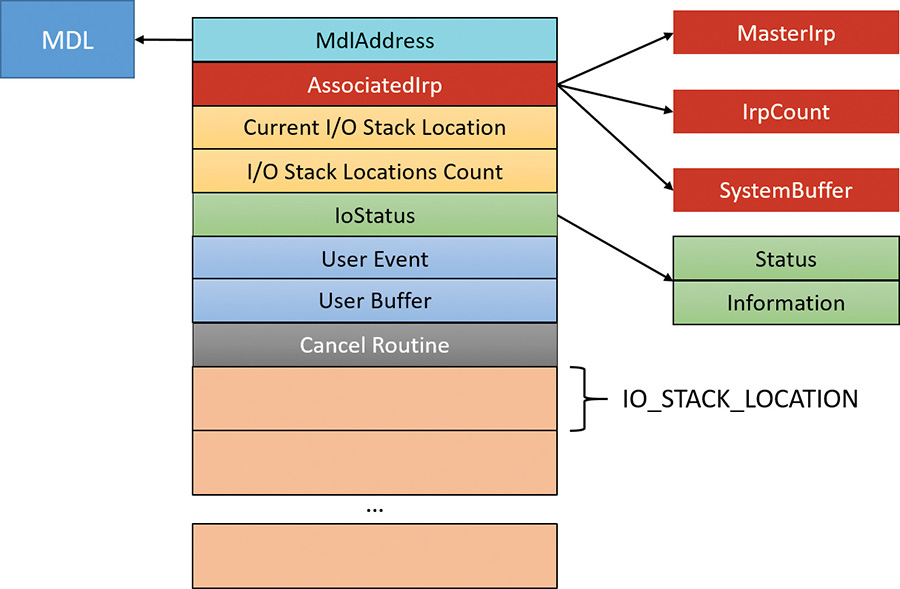

Figure 6-11 shows some of the important members of the IRP structure. It is always accompanied by one or more IO_STACK_LOCATION objects (described in the next section).

Here is a quick rundown of the members:

![]() IoStatus This is the status of the IRP, consisting of two members;

IoStatus This is the status of the IRP, consisting of two members; Status, which is the actual code itself and Information, a polymorphic value that has meaning in some cases. For example, for a read or write operation, this value (set by the driver) indicates the number of bytes read or written. This same value is the one reported as an output value from the functions ReadFile and WriteFile.

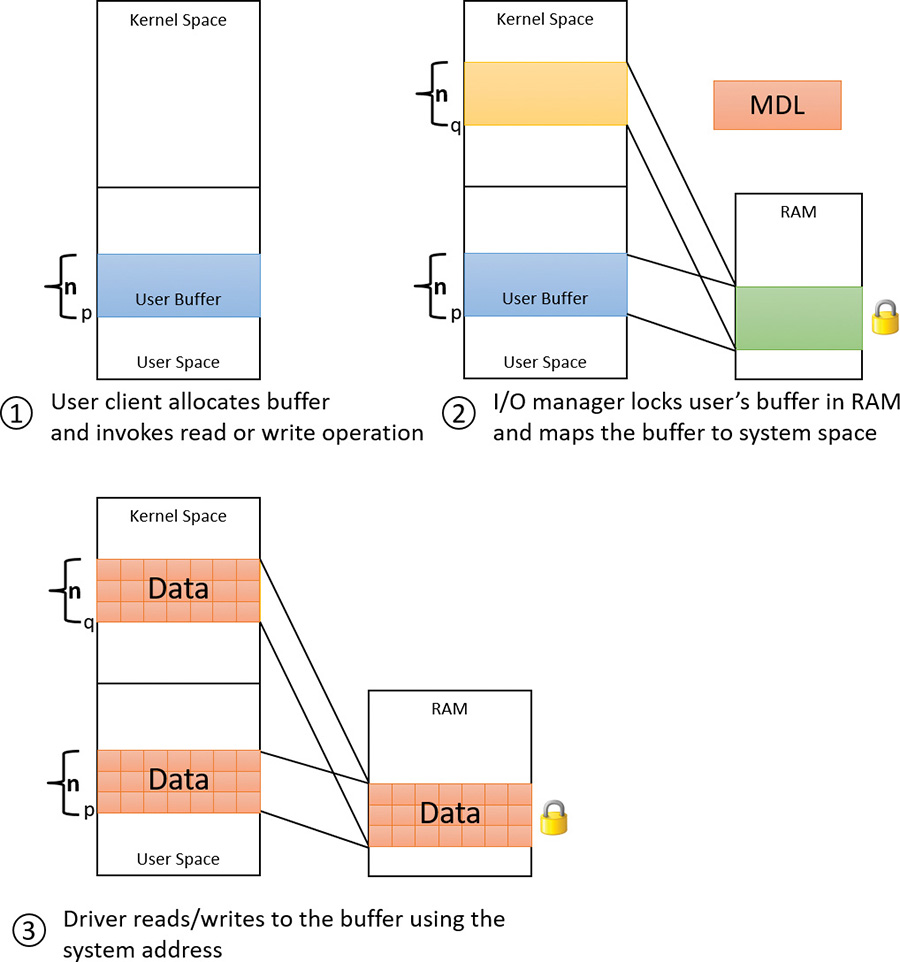

![]() MdlAddress This is an optional pointer to a memory descriptor list (MDL). An MDL is a structure that represents information for a buffer in physical memory. We’ll discuss its main usage in device drivers in the next section. If an MDL was not requested, the value is

MdlAddress This is an optional pointer to a memory descriptor list (MDL). An MDL is a structure that represents information for a buffer in physical memory. We’ll discuss its main usage in device drivers in the next section. If an MDL was not requested, the value is NULL.

![]() I/O stack locations count and current stack location These store the total number of trailing I/O stack location objects and point to the current one that this driver layer should look at, respectively. The next section discusses I/O stack locations in detail.

I/O stack locations count and current stack location These store the total number of trailing I/O stack location objects and point to the current one that this driver layer should look at, respectively. The next section discusses I/O stack locations in detail.

![]() User buffer This is the pointer to the buffer provided by the client that initiated the I/O operation. For example, it is the buffer provided to the

User buffer This is the pointer to the buffer provided by the client that initiated the I/O operation. For example, it is the buffer provided to the ReadFile or WriteFile functions.

![]() User event This is the kernel event object that was used with an overlapped (asynchronous) I/O operation (if any). An event is one way to be notified when the I/O operation completes.

User event This is the kernel event object that was used with an overlapped (asynchronous) I/O operation (if any). An event is one way to be notified when the I/O operation completes.

![]() Cancel routine This is the function to be called by the I/O manager in case the IRP is cancelled.

Cancel routine This is the function to be called by the I/O manager in case the IRP is cancelled.

![]() AssociatedIrp This is a union of one of three fields. The

AssociatedIrp This is a union of one of three fields. The SystemBuffer member is used in case the I/O manager used the buffered I/O technique for passing the user’s buffer to the driver. The next section discusses buffered I/O, as well as other options for passing user mode buffers to drivers. The MasterIrp member provides a way to create a “master IRP” that splits its work into sub-IRPs, where the master is considered complete only when all its sub-IRPs have completed.

I/O stack locations

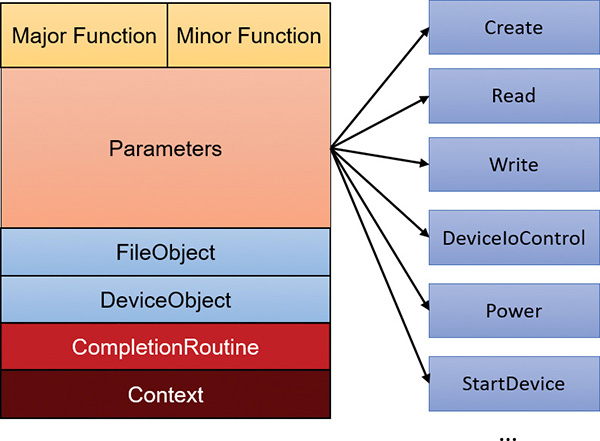

An IRP is always followed by one or more I/O stack locations. The number of stack locations is equal to the number of layered devices in the device node the IRP is destined for. The I/O operation information is split between the IRP body (the main structure) and the current I/O stack location, where current means the one set up for the particular layer of devices. Figure 6-12 shows the important fields of an I/O stack location. When an IRP is created, the number of requested I/O stack locations is passed to IoAllocateIrp. The I/O manager then initializes the IRP body and the first I/O stack location only, destined for the top-most device in the device node. Each layer in the device node is responsible for initializing the next I/O stack location if it decides to pass the IRP down to the next device.

Here is a rundown of the members shown in Figure 6-12:

![]() Major function This is the primary code that indicates the type of request (read, write, create, Plug and Play, and so on), also known as dispatch routine code. It’s one of 28 constants (0 to 27) starting with

Major function This is the primary code that indicates the type of request (read, write, create, Plug and Play, and so on), also known as dispatch routine code. It’s one of 28 constants (0 to 27) starting with IRP_MJ_ in wdm.h. This index is used by the I/O manager into the MajorFunction array of function pointers in the driver object to jump to the appropriate routine within a driver. Most drivers specify dispatch routines to handle only a subset of possible major function codes, including create (open), read, write, device I/O control, power, Plug and Play, system control (for WMI commands), cleanup, and close. File-system drivers are an example of a driver type that often fills in most or all of its dispatch entry points with functions. In contrast, a driver for a simple USB device would probably fill in only the routines needed for open, close, read, write, and sending I/O control codes. The I/O manager sets any dispatch entry points that a driver doesn’t fill to point to its own IopInvalidDeviceRequest, which completes the IRP with an error status indicating that the major function specified in the IRP is invalid for that device.

![]() Minor function This is used to augment the major function code for some functions. For example,

Minor function This is used to augment the major function code for some functions. For example, IRP_MJ_READ (read) and IRP_MJ_WRITE (write) have no minor functions. But Plug and Play and Power IRPs always have a minor IRP code that specializes the general major code. For example, the Plug and Play IRP_MJ_PNP major code is too generic; the exact instruction is given by the minor IRP, such as IRP_MN_START_DEVICE, IRP_MN_REMOVE_DEVICE, and so on.

![]() Parameters This is a monstrous union of structures, each of which valid for a particular major function code or a combination of major/minor codes. For example, for a read operation (

Parameters This is a monstrous union of structures, each of which valid for a particular major function code or a combination of major/minor codes. For example, for a read operation (IRP_MJ_READ), the Parameters.Read structure holds information on the read request, such as the buffer size.

![]() File object and Device object These point to the associated

File object and Device object These point to the associated FILE_OBJECT and DEVICE_OBJECT for this I/O request.

![]() Completion routine This is an optional function that a driver can register with the